About the Project

This project represents two parts of myself: Jacob as Nature Photographer, and Jacob as Software Engineer. What follows is a bit of autobiographical waxing poetic combined with being overly verbose. Classic Jacob.

I'm not kidding when I mention this being overly verbose. The tl;dr (too long; didn't read) is that photography has been a part of my life for 25 years, and I'm a frontend software engineer who built this project from scratch. This portfolio is built with Next.js and Typescript using Cloudinary as data host with Vercel as site host.

The tl;sr (too long; still read) can be navigated using the outline below:

Happy reading!

Jacob as Nature Photographer: From the early days to now

The Beginnings

My photography journey began when I was about 8 years old, though admittedly, it was probably more of a way for my parents to help me expend energy on family vacations. Prior to our departure, my folks would pack a treat bag full of snacks and puzzle games that were to last us the duration of whatever vacation we were embarking upon, and this included a disposable Kodak camera.

Over many trips and the efforts of my mother to turn these rolls into scrapbooks, my folks must have seen something among the mess that resulted from a small rambunctious child given free reign to photograph whatever caught his eye. It was 'round about when I was 14 that my parents upgraded me from disposable Kodak to an Olympus digital point-and-shoot.

Return to topThere just might be something in this here hobby

Not long after this, I had the opportunity to bring my shiny new camera with me on the ski slopes of West Virginia's Winterplace ski resort. After tackling one of the runs, I turned around to look back up and thought to myself that it would make a pretty picture. I pulled out the camera, fell on my stomach, and snapped this photo:

I entered this photo into a local arts competition and took first prize, to my utter astonishment and delight. This moment, more than anything, triggered my desire to incorporate photography into my definition of self.

A few months after, I was taking a hike in one of my favorite places on the planet--Cedarock Park in Burlington, North Carolina. It holds a special place in my heart for many reasons, and one relevant to this project is it's where I learned that my "photographic eye" wasn't a fluke on the ski slopes. I took a photo of the park's iconic dam-cum-waterfall that cemented in my mind that landscapes and features within nature would be my forte.

A few short years later, as a part of an art class we were directed to reproduce an image as a painting in the pointillist style. Without hesitation, I chose that photo from Cedarock Park as my subject.

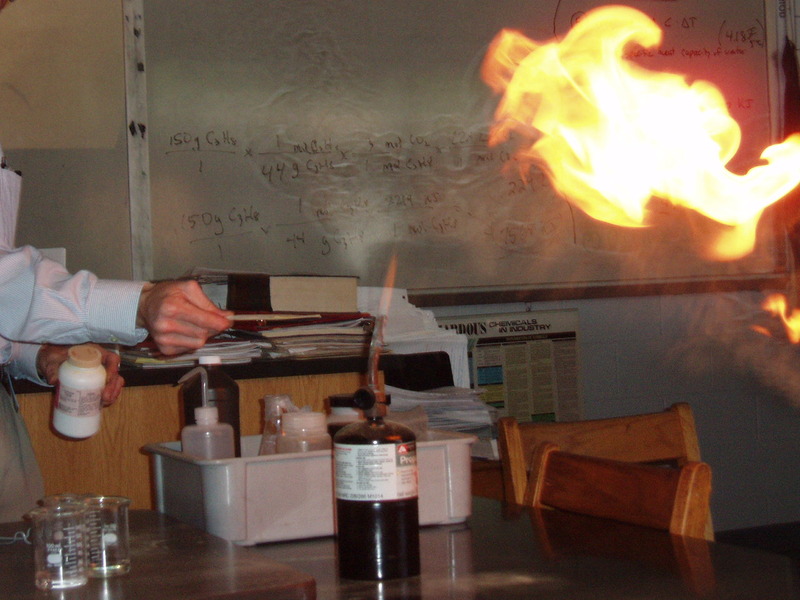

The beautiful simplicity of a digital point-and-shoot camera is how easy it is to carry everywhere. I developed a habit of sacrificing one of my pants pockets to hold this camera every single day. One might think this would lead to an abundance of photos from daily life, however that isn't how I viewed photography--I saw it as an opportunity to record the unusual, the special, the unexpected. While this means I carried it always, and used it rarely, it did mean I was prepared when in chemistry class we learned about surface area, lycopodium powder, and explosions.

In this moment I unlocked a new aspect of my photography: capturing moments of motion. It would take some dabbling in sports photography and plenty of "almost got it" experiences over the subsequent years before I would combine "movement" with "nature". But let's don't get ahead of the story.

Return to topTaking the (financial) plunge

The seed was planted about upgrading my camera once again when a family friend learned of my interest in photography. She had a DSLR (digital single-lens reflex) camera, and when my family went for a visit she suggested I give her camera a try. Aside from the joy in trying out a new camera, I was honored that someone would trust 16 year old me with such an expensive piece of equipment. I spent an entire afternoon traipsing about their garden and forested property delighting in the new views I could explore. It would take another 3 years, but I took that financial plunge and purchased a Canon 40D, with a 35-128mm telephoto lens. This was one model removed from state of the art in Canon's lineup (at the time), with the basic all-around lens for someone on a budget who wants to diversify their subject matter. An SLR or DSLR camera is special in that it allows for interchangeable lenses, enabling people to adjust their focus (pun absolutely intended!) and reach. Without needing to buy a whole new camera, a photographer can swap out compatible lenses.

Just like breaking in running shoes before a race, I learned the hard way that I should have taken the same approach with this camera. A week after it arrived, we hopped on an airplane to visit Japan. Aside from having a wonderful time as a tourist, my photographic foray there was, predictably, about on par with my old point-and-shoot. Thankfully, I had a blast with it the whole time, and so rather than be discouraged I was motivated to improve.

Fast forward six months, and I had the opportunity of a lifetime to study for a semester in Italy, with an embarrassment of riches of subject matter: architecture, art, gardens, ruins, and vistas. It was during this time that my landscape photography really began to establish itself as a cornerstone of my skillset. The majority of my travels during this time kept me in Italy, though I did take a jaunt up to Switzerland to knock off a bucket list item of snowboarding in the Swiss Alps. I took a big risk by bringing my camera with me; afterall, it's a large piece of precision equipment, and knocking it around is not generally advisable. The risk paid off in a big way, giving me both my greatest moment in landscape photography (see landscapes in the gallery), as well as in action photography (see below).

Hitting it big right off the bat like this after only 6 months of owning the camera set myself up to be humbled, experiencing my own version of the Dunning-Kruger Effect. While I saved my ego by not broadcasting to others how great I thought myself, I fell victim to overconfidence internally, and so when subsequent forays into beautiful places didn't render the same astounding results I had some emotional damage control to do. Intense self reflection combined with treating each excursion as a learning opportunity righted the ship, so to speak, and quickly converted frustrations into improvements.

I've never been one to silo myself within a specific aspect of life, no matter what it is. Whether in sports, employment, education, literature, gaming, etc., I always diversify my efforts and focus. Being a jack of all trades is aspirational to me, and my photography is no exception. Landscapes are important to me. Those vistas are the elements of nature which put me most at ease, which deliver contentment and mental stability and peace. And yet there is so much more I can explore with photography than just that one aspect. Where else could I find my zen? What types of photography challenge me while simultaneously leaving me fulfilled?

I tried to get artistic with it. I pulled it off just the once, really, with some terracotta roof tiles in Sicily, Italy. I put myself into an unreliable position at the top of Monreale's cathedral to take this photo. At least this time I knew it was a special moment, and not some bit of inherent skill that nabbed me this one.

Knowing it was a special moment didn't stop me from trying time and again to replicate the outcome of the photo above. Alas, it never seemed to turn out the way I'd see it in my mind. Even though getting artsy with objects didn't pan out as I thought it might, it was excellent practice for my soon-to-be-discovered passion for shooting (with a camera!) wild creatures. Much of what I've included in my photo gallery requires looking at things and seeing what others pass right over. What I need to do to take an artsy photo is what I need to do to capture an invertebrate, a sneaky bird, or a hidden fungus.

I tried portrait photography, which was fun, but very stressful. People seem to generally want to look different than they really are. Either they actively want perceived flaws obscured or removed, or they don't realize what they look like in someone else's eyes. After all, we generally only see ourselves in a mirror and the occasional selfie. It may help us get ready for the day, but it is an incomplete picture (pun totally intended!) and I didn't want to deal with the stress of managing expectations and outcomes on top of everything else. When it comes to taking people's pictures, I'll stick to candid snapshots, like the one below.

I tried sports photography. After all, that snowboarding photo was totally rad. I certainly gave myself plenty of attempts at it, as I brought my camera with me to football games, pickup soccer, rope swings, lacrosse games, and disc golf adventures. Each type of outing was just on the edge of hitting that feeling I was chasing. Even if I didn't settle on this as my path, I still got a kick out of it.

I haven't given up on sports photography. I find it a fun challenge, and will occasionally bust out the camera when I find an opportune moment. It's on the backburner for now, though I'll keep pestering and poking at it from time to time, just to remind myself. Like what this Syracuse defender is doing to the Duke player here.

I dabbled and explored, though nothing seemed to bring a sense of completeness. Despite everything that I was doing--and enjoying! Don't get me wrong there, I was loving it all the while--I had only found flowers to complement landscapes as something I loved to do, as something that delivered that contentment.

Bodies in motion. That's what I wanted to shoot. And while I still bust out the camera for a little sportsing, I've found that the bodies in motion that really hit the spot for me are not human bodies. Rather, they are the mobile elements of nature.

Return to topConnecting with nature

From the time I learned of the BBC's Planet Earth in 2009 (thanks to the cool dude rockin' the Clemson t-shirt pictured above) I've been fascinated with natural history documentaries. Living in the US and pining for content from the UK generally meant being left wanting. Only the big productions were made available internationally, and so all I was aware of were those landmark productions featuring box-office names as narrators. Anything I found that was not narrated by a Hollywood icon or my hero, Sir David Attenborough, I stumbled into by roundabout means. Here are the ones I managed to get my hands on over the years:

- (2006) Planet Earth, narrated/presented by Sir David Attenborough

- (2006) Galápagos, narrated by Tilda Swinton

- (2007) Earth: The Power of the Planet, presented by Iain Stewart

- (2008) Wild China, narrated by Bernard Hill

- (2009) South Pacific, narrated by Benedict Cumberbatch

- (2009) Life, narrated by Sir David Attenborough

- (2011) Human Planet, narrated by John Hurt

- (2011) Frozen Planet, narrated by Sir David Attenborough

- (2013) Africa, narrated by Sir David Attenborough

- (2016) Planet Earth II, narrated/presented by Sir David Attenborough

- (2017) Blue Planet II, narrated/presented by Sir David Attenborough

This fascination with BBC-produced nature documentaries took hold in a big way in 2019 as I found sources for much of the BBC's legacy content and "smaller" programs, which led to me binge watch these nearly every day for over a year as I worked through the catalogue. Y'all, there are hundreds of these! Most pivotal for me during this period was exposure to their annual Watch series--Springwatch, Autumnwatch, and Winterwatch--whose focus turns in a different direction than the major productions to which I was accustomed. Rather than being centered on "exotic" wildlife from remote locations, the Watch series is all about local nature and wildlife, those things folks can observe themselves without great expense or difficulty. It flipped a switch in my mind: I could do this too; I have local wildlife, I could do my own exploring! It seems like a no-brainer after the fact, but up to this point photography to me generally meant a big effort excursion. And with memory being the fragile thing that it is, I prefer to record my observations as digital memories so that I can revisit them as time goes by.

But what could I do about it? There were plenty of chances to stop and photograph the roses, which I've done quite often, and it wasn't leaving me terribly satisfied. I felt restricted to the beautiful, but immobile, side of the natural world. With patience and determination, I kept at it, still with that 35-128mm general purpose lens. Lenses are super expensive, so buying one on a whim wasn't something I was prepared to do. After all, what if I get the wrong one? What if I went for a macro lens and then found myself aching for long distance photography instead? What if I opted for a mega zoom upgrade, but then realized that I would much prefer to get up close and personal with the little things in life? I felt stuck.

Serendipity has played a key role in my life as a photographer. Each step in this journey has been guided by a trusted adult saying something equivalent to, "would you like to try with this?" The first step was when my parents gave me a disposable Kodak. The second was when they gave me a digital point-and-shoot. The third was when a family friend let me try out their DSLR to see how I liked working with that type of camera. And now we come to step number four: my brother's father-in-law is a talented photographer himself. We all happened to be gathering by a rural lake in Virginia for a few days in the summer of 2019, and he watched me out stalking for something to photograph. After watching me try and fail to get close enough to some birds, he walked over with his camera bag, unzipped it, pulled out a massive telephoto lens and said, "would you like to try with this?" We both shoot on a Canon, so the lenses were compatible, and I felt like my teenage self all over again being trusted with a prized piece of equipment.

I felt like I had been given glasses after a lifetime of fuzzy vision. I was grinning from ear to ear with just how much range I could get! The clarity and focus of things so far away brought near was such a fabulous experience. I was no longer at an impasse; I knew which direction I wanted to head. All I had to do was save. A lot. Patience, Jacob. Patience.

Return to topTaking the (financial) plunge redux

Also known as: new lens, new me.

It took two years of saving before I was in a position to upgrade to a new lens. I did extensive research of the different types of lenses, and what I could expect from them. There was one photographer's blog who wrote a really in-depth analysis of several of the lenses I had narrowed it down to (alas, I forgot who it was or I'd link it here). Based on what he wrote and how he presented his test data and experimental efforts I was decided; I would get a 400mm lens. Aside from greater reach, this would always be at the 400mm mark, whereas my existing lens allowed me to vary that from 35 to 128mm; so basically greater reach with reduced lens versatility. I was pumped, and couldn't wait to buy it. I went to one online retailer. Oh, no, this isn't good. I went to another just in case. Oh, no, no. I went to a third to confirm the pattern. Oh, no, no, no. That lens costs as much as a quality used car. Oof.

Okay, back to the article to revisit what he wrote about my second option, the 100-400mm lens. I'm no technical expert when it comes to photography, so I make some assumptions I probably shouldn't. What this means is that initially I assumed the 100-400mm was much better and, thus, far more expensive. Therefore, I had set that aside in favor of the lens that would still be good for me, but hopefully at a friendly-to-Jacob price point. Thankfully, I was very wrong. Coincidentally enough, the 100-400mm lens's focal length covers a range of a factor of 4 and that was also the price variance between the two lenses I was comparing. It was as if having the capability of modifying the focal length by 4x also reduced the price by 4x as well. I think the real reason is that the increased versatility leads to some loss in comparative quality, but that might not be the complete picture (pun intended!).

Even though the lens I ultimately chose was four times less expensive, it remained a large financial investment. Like many things in life, in order to pursue one thing, we must refrain from pursuing another. In economics this can be referred to as an "opportunity cost". Though it may seem like I'm being cavalier about upgrading to a very expensive lens, the reality is it was a culmination of careful long term spending and saving, as well as forgoing future luxuries for a time. Some might not think a camera lens worth it, but for me this has been life changing.

I'm not being hyperbolic here. Because I made this purchase, I am more connected to the natural world; I'm finding contentment and mental stability and peace from more than just sweeping, grandiose vistas I mentioned previously; I see the fragility and beauty in all that surrounds us; I'm constantly learning more about how interconnected life is, and how it's far more complex than I could ever hope to convey; I feel a sense of urgency regarding climate action (or lack thereof) because I feel better able to see just how we continue to senselessly damage and destroy our environment.

This last bit is the ultimate reason for this portfolio. It's a means to bring these emotional experiences and sense of wonder to a wider audience. It's my own small effort to replicate for others what those BBC natural history documentaries have done for me. Which is to say, when you can see the detail and put a name to a thing, you might feel more connected to that thing, and emotionally invested in its wellbeing. And it's particularly critical for those elements of nature that are essential for a healthy ecosystem, but we humans tend to treat as pests.

Return to topWhat's that thing?

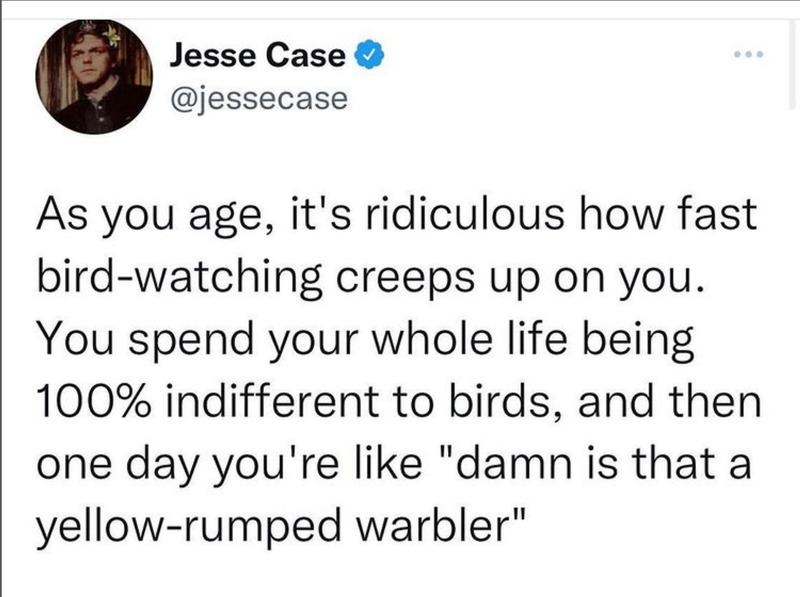

Of course, in order to achieve my goal here I first must correctly identify what it is I have captured. I want to be able to go from "hmm yes, the floor is made of floor":

to "damn, is that a yellow-rumped warbler?"

A fun aside, my sister sent me that screenshot as I was literally standing on a birdwatching tower in Estonia...

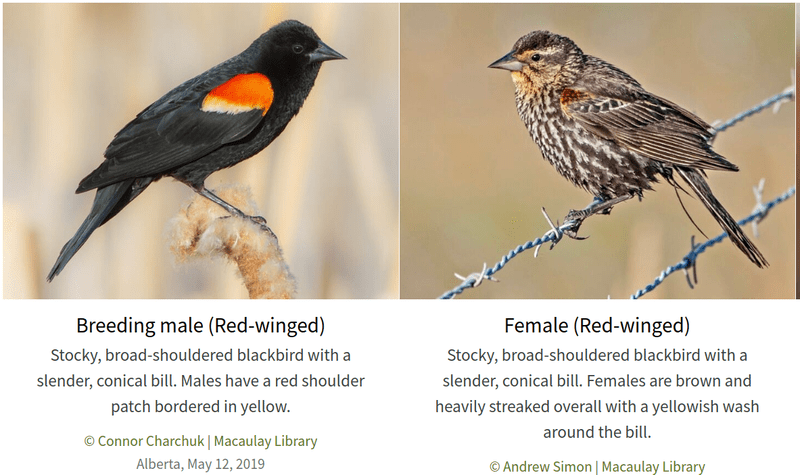

There are two phenomenal tools I use to make identifications. Both are 100% free. As birds can exhibit radical sexual dimorphism, where the males and females look totally different, I find it helpful to use Merlin, an app built and published by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Using this app I can input a few data points and be supplied with possible options for what I observed. What makes this particularly helpful is the inclusion of high quality images for each bird, and a definitive label for the sex of the bird in that image. Fair warning: the app takes up loads of space on your phone. It is a tool designed to facilitate observations independent of reliable internet access, so the data gets stored locally on the phone. They reduce the space requirements by organizing their data into regional packs. For example, I have "US and Canada: Continental" as well as "Western Palearctic" currently installed.

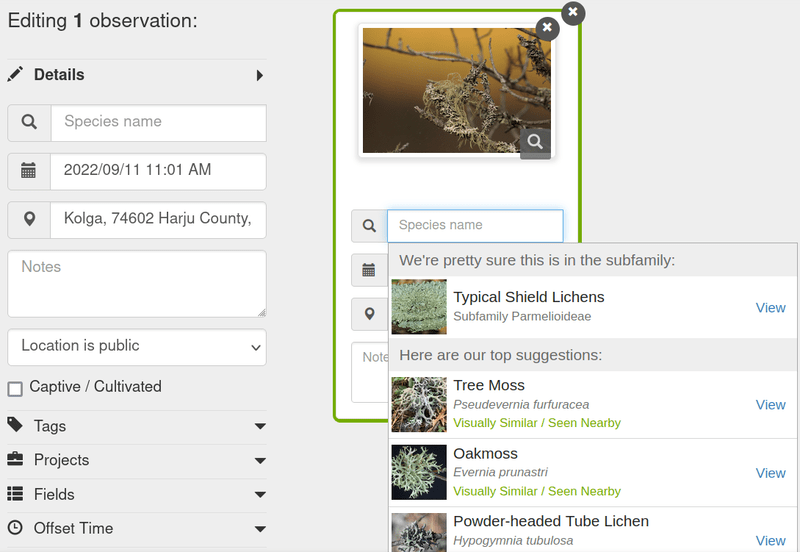

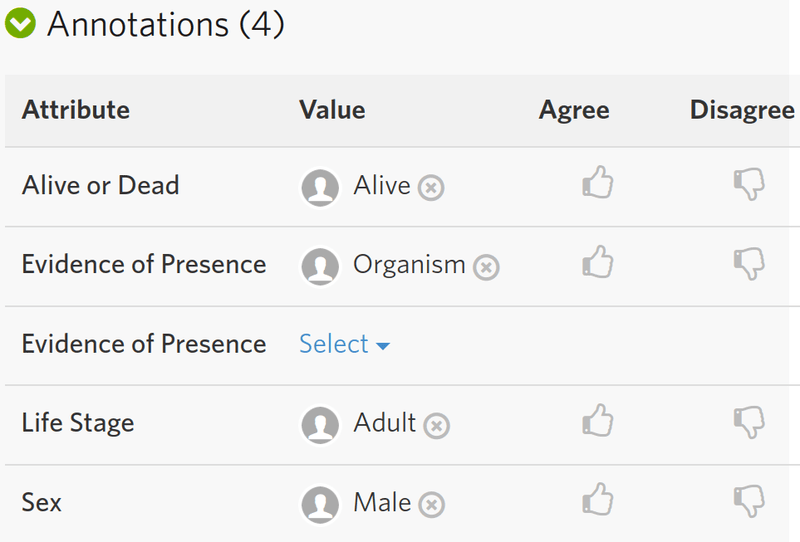

In addition to Merlin, I use iNaturalist to make identifications of pretty much everything else. The approach I use here is to upload an image I have taken, mark where I observed it, and see what their machine learning algorithm suggests. It's usually very good at getting close to what's in the picture. The benefit of iNaturalist is how community-centric it is. I can upload something and say that it's an eastern carpenter ant, but that doesn't mean jack until two other users come along to confirm my identification. This method improves the quality of observations by adding confirmations and correcting errors.

Between these two resources I can usually get the ID I need. On very rare occasions I'll venture over to Reddit and ask there, which is what I did before some kind user pointed me to iNaturalist. I have a preference for which interface I use, though. For Merlin, I much prefer their mobile app, as I'm usually marking the ID elsewhere for future reference, and not actually uploading the image I've taken. For iNaturalist, I much prefer their desktop browser interface. It is a better user experience, and I can include other helpful data annotations more easily than I can in mobile. I can also more easily review ID suggestions without losing my place in the upload process or committing myself to an incorrect identification that I'll subsequently need to rectify.

Regardless of which tool I've used to identify what I've observed, when it comes time to include one of my best-of's in this portfolio I will use iNaturalist to get the scientific name. Common names may vary from region to region, and language to language, but the scientific name is the universal descriptor. By including this with my caption, I'm enabling anyone who's perusing this site to find that precise species independent of their native language.

Return to topThe end?

For this write-up on Jacob as Nature Photographer, perhaps. Certainly not in regards to my photographic endeavors, which I feel are only just beginning. It's an odd thing to type, considering my 25 years of photography thus far; there's just so much more to explore! Will there be yet another (financial) plunge in my future where I pick up a macro lens so I can get even more immersed in the invertebrate world? What forays can I embark upon, both near and far? What new fascinating aspects of the natural world will I get to experience? My new favorite biome is wetlands, especially after having a blast traipsing about bogs and mires in the Baltic in 2022. I haven't done much of that type of exploring in my native USA, so that's certainly a focus point for me. Who knows?

All I can say is that I'm excited to find out.

Return to topJacob as Software Engineer: No early days, just now

Engineering overview

I write front-end code, and I focus on digital accessibility. I aspire to be a more well-rounded engineer so I can always be helpful on either side of the software stack, which makes sense as I crave understanding the "whys" behind the "whats", and deeper understanding leads to more versatility and usefulness. I derive much greater satisfaction in highlighting the successes, the wins large and small, of my colleagues than I ever do in highlighting my own. My existing projects are written in JavaScript or TypeScript, and usually leverage the React framework for frontend interactivity.

In an ongoing effort to become that well-rounded engineer I easily find myself bouncing from one thing to the next. Should I learn python or Go? Should I dive into Node or Ruby? Hmmm, perhaps I should explore something related to database management? Choice paralysis hit pretty hard here. How would I break the impasse?

Return to topBeginning to build this portfolio

🎶 It started with a whisperrrr... 🎶

Wait, no. It started with a tutorial. I decided to learn more about backend engineering, to get re-exposed to Nodejs & Express as a way to strengthen my overall engineering self. I found a video from Chris Blakely covering full stack development with React / Node / Express to build out a photo gallery using an API called Cloudinary, which I had never heard of before. Given my background (see the wall of text above) I was immediately interested. Afterall, one of the fundamental things about how I learn is to establish a personal connection to the subject matter. I like coding along with tutorials like this one as a way to learn how other people structure their code, and how they go from a blank file to a completed project. And once I've reached the end of a tutorial, I take it further: Is it accessible? Are there edge cases that need to be considered? How can I expand upon or otherwise modify what I coded along with? Can I incorporate something from one tutorial into another one? Are there projects I have already completed that could be refactored with my new experience?

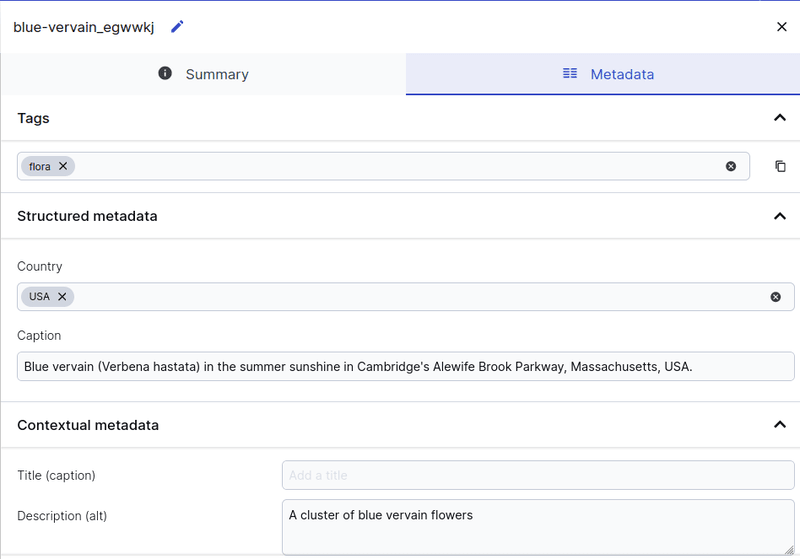

This project was no different, and I decided that rather than use JavaScript as the base language like the tutorial did, I would use TypeScript instead. Additionally, as I was tinkering with other ways to go beyond the tutorial, I decided to upgrade this from a practice project to something I wanted to publish to the world. More specifically, the idea took root when I was exploring Cloudinary's capabilities. One of the key requirements for including images on a webpage is to include alternate (alt) text to go along with it. This is required for people who use screen readers to understand what the image is supposed to represent, and is generally helpful in case images are slow (or otherwise fail) to load. Every image includes metadata with it, and some will have more than others depending on how the image was created. For example, a photograph's metadata will include time & date information based on the camera's settings, information about the camera itself (make & model), as well as settings used at the time of capture (ISO, f-stop, shutter speed, etc).

The metadata that's required, but does not get generated automatically, is the alt text. In searching for a way for me to link images I'm hosting on Cloudinary with useful alt text, I learned that Cloudinary includes support for custom metadata fields. This means that within their environment I can add information to an image I have uploaded, so that when I pull it in to display in this here project, I have access to that custom data as well. Not only was I able to include alt text for each image, I was also able to tag the images, mark the country, and write a photo caption to describe the image and provide any additional context I feel may be required. Once I learned I could have this kind of flexibility within Cloudinary's environment I decided to build this as a serious demonstration of both "Aspects of Jacob."

There's a package for that

One of the things I wanted to achieve with this portfolio is an intuitive way for a user to open an image in full screen mode on desktop or tablet. Even though I built this portfolio to be consumed on desktop, tablet, and mobile, this particular feature doesn't make much sense for mobile. After much trial and error and lost hours googling for tips and tricks, I remembered about the cornerstone of software development: open-source code. Surely there is someone out there who has built a project using the React framework who also wanted to achieve the same thing as me, and it was my hope that one of those someones published a package for others to use. Yes, there is! Huzzah!

I was able to incorporate this into my code. I was finished with this key component! Or was I? Alas, a perfect solution was too much to hope for.

There were two pieces absent from this package, one of which is mission critical. While their code allowed for supplying dynamic image information so a user could go from one image to the next, it hard coded the alt text to be an empty string. An empty string representing a deliberate absence of alt text is only acceptable for non-essential images. So it's particularly odd for this package, as the whole point is that the image is significant. I either needed to find a new source, or I could tweak it by hand. I chose the latter.

With open-source packages comes visibility of the underlying code itself. My best recourse here was to copy in what I'll refer to as the baseline code, so that I could then force it to support basic accessibility practices. That resolved the mission critical piece. As I had pulled in the baseline code, I was then able to modify the entire structure of the component, so instead of simply being a full-screen image, I built in support for image context, like captioning text. Oh, hello Cloudinary custom metadata! It's good to see you again! Here's a simplified version of that modification:

//BEFORE:

<div className="content" onClick={handleClick}>

<div className="slide">

<img className="image" src={props.src[currentIndex]} alt="" />

</div>

</div>//AFTER:

<figure className="figure" onClick={handleClick} tabIndex={0}>

<img className="image" src={image.secure_url} alt={image.context?.alt} />

<figcaption className="caption">{image.metadata?.caption}</figcaption>

</figure>Even if you don't know much about code, you can look at this and understand semantically what's going on, and how figure / img / figcaption makes more sense and looks cleaner than div / div / img, while providing additional information via that caption. Semantic elements like this facilitate code interpretation by assistive technology, which makes this a win-win for both developer and user.

I made a design decision about how to display this caption. I did not want to sacrifice screen space by appending it below the image similar to what you may see on a news article (and how mobile users will experience this portfolio); I wanted this to hover over a portion of the bottom of the image. I also wanted to allow the user to "dismiss" the caption and view the image without obstruction. I could achieve this by using a simple hover effect, so that when a user mouses over the image the caption appears, but this leaves out anyone who is navigating via keyboard.

The first step was to make the full screen image focusable, which is not a default setting for image content. This then gave access to the keyboard for triggering the caption to appear. But I still had a bit of a UX gap here. A mouse user could "stumble upon" the caption and make it visible, thus knowing this was an option. However, that is not a reliable method for keyboard users to interact with the content. I needed a way to start with the image receiving focus upon going into full screen view so that the caption will be there by default--no need to discover that feature. And then the caption would disappear upon shifting focus away from the photo to one of the left/right navigation buttons.

After much trial and error and lost hours googling for tips and tricks, I remembered about the cornerstone of software d... Wait, this feels familiar... I know what to do! I found a package called focus-trap-react that, in this case, did perfectly suit my needs. In addition to applying focus to the photo when opened into full screen, it returns the focus to whichever element had focus when the trap was activated. Wahoo!

Next.js, a new-to-Jacob framework

When it came time to deploy the project into production, I realized I hadn't taken into consideration what it means to have a full stack application running live. I learned there's a big gap between local development and live deployment of a server. The scope of the project had also changed along the way--from practice project to full-fledged portfolio--and that first iteration was over-engineered. More specifically, I did not need to support a user's ability to make modifications to my database, such as adding, changing, or deleting images. I came to the conclusion that I was going about it all wrong. I took a page from the startup playbook, and tore it all down to rebuild from scratch, using a different tech setup.

While I did not need to support a server being live all the time, I still needed to execute server-specific tasks. Next.js is a frontend framework built on top of React, and solves this problem specifically. It provides a framework experience and natively supports serverless functions so that data can be fetched securely without the financial and environmental costs of keeping a server up and running at all hours of the day. The only hangup is that I didn't know Next.js, so I would need to, once again, jump into tutorial land to learn the ins and outs of this framework.

Some basic searching turned up an entire Next.js for Beginners series by Dave Gray. Don't be fooled here, "beginners" means folks who are new to Next, not folks who are new to coding. Just like working with React requires a solid foundation in JavaScript, Next requires a solid foundation in React. After working my way through this course--and major props to Dave for being such a good teacher--I was able to hit the ground running, and convert my full stack React/Node project into a frontend project, featuring client components, server components, and serverless functions.

While this was originally a full stack practice project designed to teach me more about backend coding that turned into a frontend portfolio without a dedicated backend, I learned far more about the backend by implementing serverless functions than I did from that original React/Node tutorial. My data in Cloudinary is protected behind my user information. In order to access that for this portfolio, I needed to be able to tell Cloudinary that this application is in fact authorized to retrieve that data, a task normally outsourced to a backend. Both Next.js and Cloudinary have built-in protections to block anyone from improperly executing a data fetch to protected content, and will throw errors when a fetch is called in an unsafe manner. Though serverless functions make it sound like it has nothing to do with backend code, they are in fact extracts of server-side code that will run without needing a dedicated server. As Vercel, the company that created and maintains Next.js, puts it:

Serverless Functions enable developers to write functions in JavaScript and other languages to handle user authentication, form submissions, database queries, custom Slack commands, and more.

These Functions are co-located with your code and part of your Git workflow. As traffic increases, they automatically scale up and down to meet your needs, helping you to avoid paying for always-on compute with no downtime.

Unraveling error messages as I attempted to leverage these serverless functions--a form of error-driven design--drove a deeper understanding of the backend, how it functions, and how to interact with it.

Once I got that element functioning properly, I was off to the races. After all, I had a working prototype using React, so transposing that code into the new format was mostly straightforward. It was at this point that I was firing on all cylinders, cranking out quality code at a pace I had not achieved before. And then I got to the deploy step, a bit nervous after my last attempt, and it went off nearly without a hitch! A few minor tweaks was all it took to get this project live and hosted on Vercel, and I'm beyond ecstatic to share it with you.

Return to topWrapping up

Being on my own, building a passion project that has stretched my skills, I've felt sustained pressure, like I'm an imposter or that I don't really know what I'm doing. It's easy to get down on myself. After all, I am my own toughest critic. So to feel it all come together, to feel it flow has been the greatest validation of Jacob as Software Engineer. As I type this, I'm honestly holding back tears.

I feel comfortable positing that most software engineers experience emotional extremes over the course of a project, and can appreciate why the culmination of this project has affected me so. Add in the nostalgia of revisiting the last 25 years of my life to write this mini-memoir (see Jacob as Nature Photographer), and it's perfectly understandable that I feel I've been put through the wringer. I'm hopeful that any non-engineer reading through this can also relate, which would indicate that I've done well enough as a writer, too.

And so now I leave you, friend, with this final thought inspired by a meme I saw once:

May you be as positive and forgiving of your "happy little accidents" as Bob Ross.

May you cultivate an endless passion for learning all things like Carl Sagan.

May you be as kind to yourself and your neighbors as Fred Rogers.

May you love all things in nature as passionately as Steve Irwin.

Have a great day!

Return to top